OK. It finally happened.

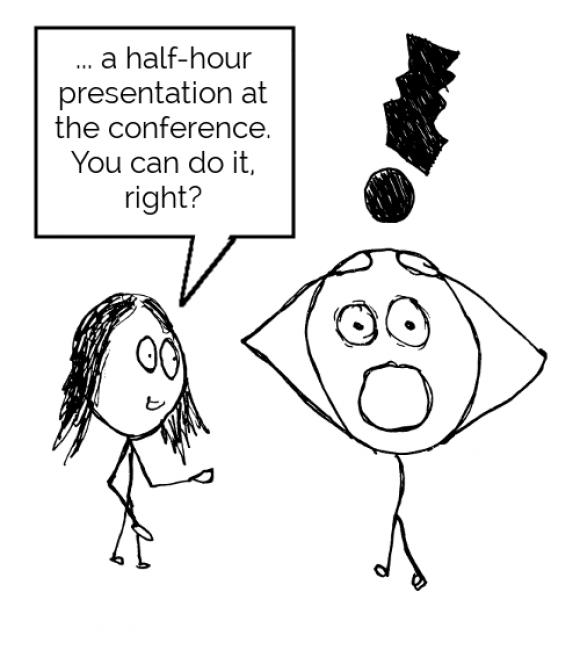

You need to give a half-hour presentation in front of hundreds of people.

And you’ve never talked about anything in front of more than ten people before in your life.

In fact, you almost fainted when you had to give a small speech on your birthday in front of a few friends and family.

And now you have to talk in front of a whole room. For half an hour. By yourself!

Well, don’t panic!

All you need to do is take a deep breath, grab your coffee (or green

tea), and follow these simple but effective pieces of advice.

If you do that, you will turn your fear into something truly awesome.

There are two main parts of doing a presentation: what you do before it, and what you do during.

Today we’re going to look at what you can do beforehand in order to make your presentation the one everyone remembers.

1. Prepare!

It sounds obvious, right?

But it’s by far the most important thing on this list.

But what does preparation mean?

Well, it falls into two simple categories:

Know it – know it all!

I remember when I was going to give my first talk at a conference, my

dad, a well seasoned public speaker, gave me some great advice.

He said, “Whatever happens, make sure you know more about the topic than anyone else in the room.”

I took that on board and did loads of research – much more than I needed.

But it was worth it!

My script was neater, I learned more, I become more passionate about

the topic and, most importantly, it gave me the confidence of a bear

fighting a drunk koala.

“All that research? Surely it’s wasting time when I could just be writing the damn thing?”

Not true.

The more time you spend researching it, the easier (and quicker and

more enjoyable) it will be when you come to actually writing it.

In fact, it’ll just write itself!

Practise, practise, practise

This one’s obvious, too, right?

But so many people don’t do it.

I understand why.

I mean, it’s really easy to write something and then imagine yourself

doing it – you see yourself walking on the stage and delivering the

awesome talk you’ve just written.

You imagine the crowd laughing in the right places and looking serious in the right places.

It’s easy to imagine it all, right?

But it doesn’t work like that.

You need to do it. A lot. Until you’re physically sick of it.

Do it in front of the mirror. (I personally hate doing this, but it really helps.)

Do it in front of a friend or partner.

And if you can, try to set up a small rehearsal and do it in front of a small group of friends.

You’ll be surprised how much of a difference it’ll make.

2. Don’t go nuts with the PowerPoint slides

There are two ways we use PowerPoint slides:

For images and for text.

The images

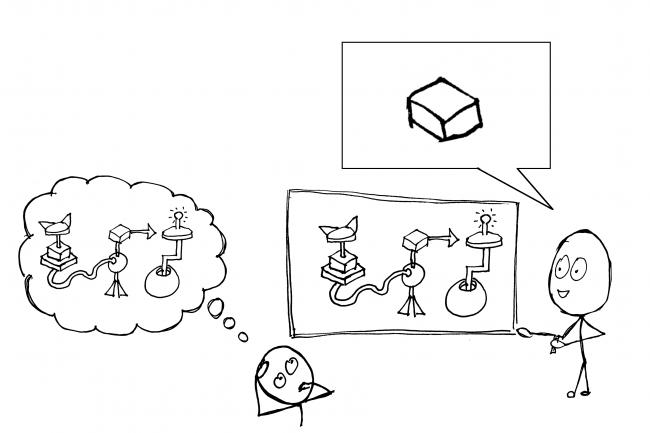

Images are there to enhance your message – not to deliver it and certainly not to distract from it.

Use images that will give strength to what you’re trying to say, but

as soon as they become irrelevant or, even worse, decorative, then cut

them out.

If you’ve watched many talks and presentations, you might be familiar with this feeling:

When it comes to images, keep it simple.

The text

There’s a mistake I see ALL the time when I watch people give presentations with slides.

And it drives me nuts!

I’m sure you’ve seen it too:

You’re watching someone give a presentation. They bring up a slide

full – I mean FULL – of bullet points. Bullet points consisting of full

sentences – sentences with lots of adjectives and clauses and

everything.

Then they start speaking.

And they’re just reading exactly the same words that are on the slides.

What’s the point? They might as well simply just stand there and let us all read the slides. Why are they even there?

Don’t make the same mistake!

The slides are there to provide a bit of structure and to give you a framework.

The slides are not your script.

If you do this, you will die a slow death on stage.

I told you it drove me nuts!

3. Get the script right

So what are you actually going to say?

There’s a lot of advice out there, but here are the essentials.

Start with a “grabber”

You’ve watched TED talks, right?

Have you noticed how they always start with something that grabs your

attention, so you end up having to watch the whole talk, even if you

were only planning on watching the first five minutes?

Sometimes it’s something weird, like “When I was an elephant, I never thought about flowers the right way …”

Sometimes it’s an amazing fact that you just can’t believe, like “Did

you know that you can recognise all 40,000 types of dolphin face with

one simple trick?”

Or sometimes it’s that little problem that needs solving at the beginning of the talk.

These little introductions are called “grabbers” – because they grab your attention.

Grabbers can be difficult to write, and there are loads of different

ways to write them, but if you want to keep it simple, the classic is to

think about the conclusion of your presentation, turn it into a

question and make that question your grabber.

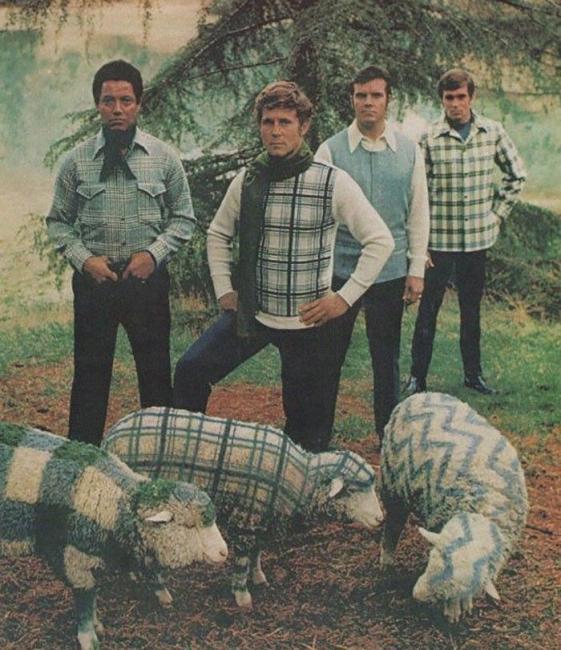

I once did a presentation on 1970s experimental teaching methodologies.

Now, I’ll be the first to admit that that’s quite an obscure topic.

Not something that my audience thought about on a daily basis.

I needed something to get them switched on to the topic from the beginning.

My grabber was to throw up a picture on the projector from the 1970s that highlighted how weird and mad that decade was:

Then I said something like, “The 1970s! Ridiculous! Or was it?”

I went for the “or was it?” grabber.

If you’re doing a talk on something more serious, this approach can still work.

Imagine you’re doing a talk on integrating the marketing and sales departments. How would you create a grabber?

How about this: “Marketing and Sales. Two completely independent departments. Impossible to integrate! Or are they?”

Whatever you do, don’t start with: “Today I’m going to talk to you about …”

Unless you enjoy watching a room full of people falling asleep very quickly.

Structure your presentation

It’s quite helpful to imagine your presentation in sections.

A lot of people recommend a three-part approach: the grabber, the

main body, and the closer (where you might refer back to the grabber).

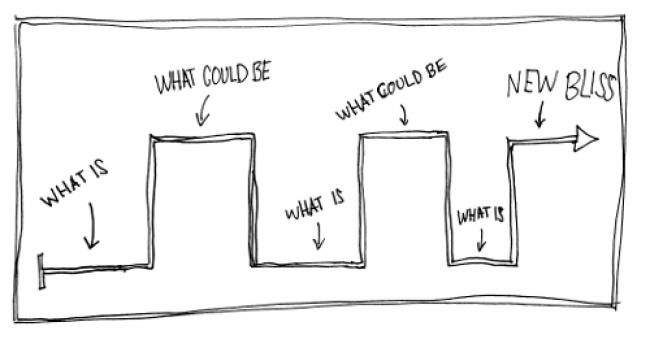

If you want to go for a particularly inspirational approach, you could try Nancy Duarte’s “sparkline.”

Here’s a link to a detailed description, but to summarize, the sparkline structure is all about taking reality and consolidating it with possibility.

You start with “what is” (for example, “our society is falling

apart”) and move on to “what could be” (like “we could fix everything

with carrot cake and also learn to fly”).

You do this a few times, jumping between what’s happening and what you want to happen.

The key to this structure is finishing on the “what could be.”

This creates a sense of possibility and motivates the audience, which will make them love you forever.

Or at least until the free coffee after the conference.

Don’t read from a script

This one is simple.

When you read from a full script, with every word written down, you’re less likely to look up to the audience.

You’ll look like you’re more interested in the piece of paper in your hand and not in the people in the room.

They’ll feel that, and then they’ll switch off.

The way to avoid that?

Try to write everything in the form of notes and bullet points – not full sentences.

And if you can, memorize those notes and go on stage without anything except your clothes and your brain.

If you can do this, it’ll achieve two things:

You’ll be able to give your full attention to the audience, and they’ll appreciate you for it.

You’ll also feel free! This means you can put more passion and focus into what you’re saying.

Use techniques that humans instinctively respond to

There are a few things that we, as humans, react strongly to.

For example, notice how differently you respond to these two sentences:

This one:

“I’m going to tell you why carrot cake is the most important thing in the world.”

And:

“Do you know why carrot cake is the most important thing in the world?”

The difference? Questions!

It’s a simple thing, but when someone asks us a question, we automatically think of (and sometimes say) the answer.

It makes the audience interact with you, even if it’s just happening in their heads.

Another thing that humans respond better to is stories.

If you use metaphors, similes and personal stories, the audience will

find it easier to follow what you’re saying and will love you for it.

Let’s take a sentence like this for example: “It’s important to practice if you want to learn a new language.”

Pretty boring, right? It doesn’t really inspire you to go and learn a new language.

Now, what happens when we add a couple of similes and metaphors?

“Learning a new language is like learning a musical instrument: the

more you practice, the better you get and the more beautiful you sound.

You can become the Mozart of Lithuanian if you practice hard enough.”

Much better, yeah?

OK. So now you’re ready to go into that room, get on stage and impress the hell out of everyone.

But what now?

Don’t forget to check out part two of this article to find out my four simple tips to help you during your presentation.

Did you enjoy reading this article? Here’s more advice on effective public speaking.

Making Public Speaking Easy #2: The Big Day

Making Public Speaking Easy #3: Post Mortem

Gabriel Clark, LOS Consultant & Clark and Miller Co-founder