What on earth is an exonym?

Good question!

Let’s answer it by thinking of Germany:

If you translate the word “Germany” (or “German” come to that) into your own language, you’ll probably find that it doesn’t sound like the word “German” at all.

In fact, looking at this list, you can see that there are LOADS of ways to say “Germany” depending on where you’re from:

And what do Germans call Germany?

“Deutschland,” of course!

Which also sounds nothing like “Germany.”

So what’s going on here?

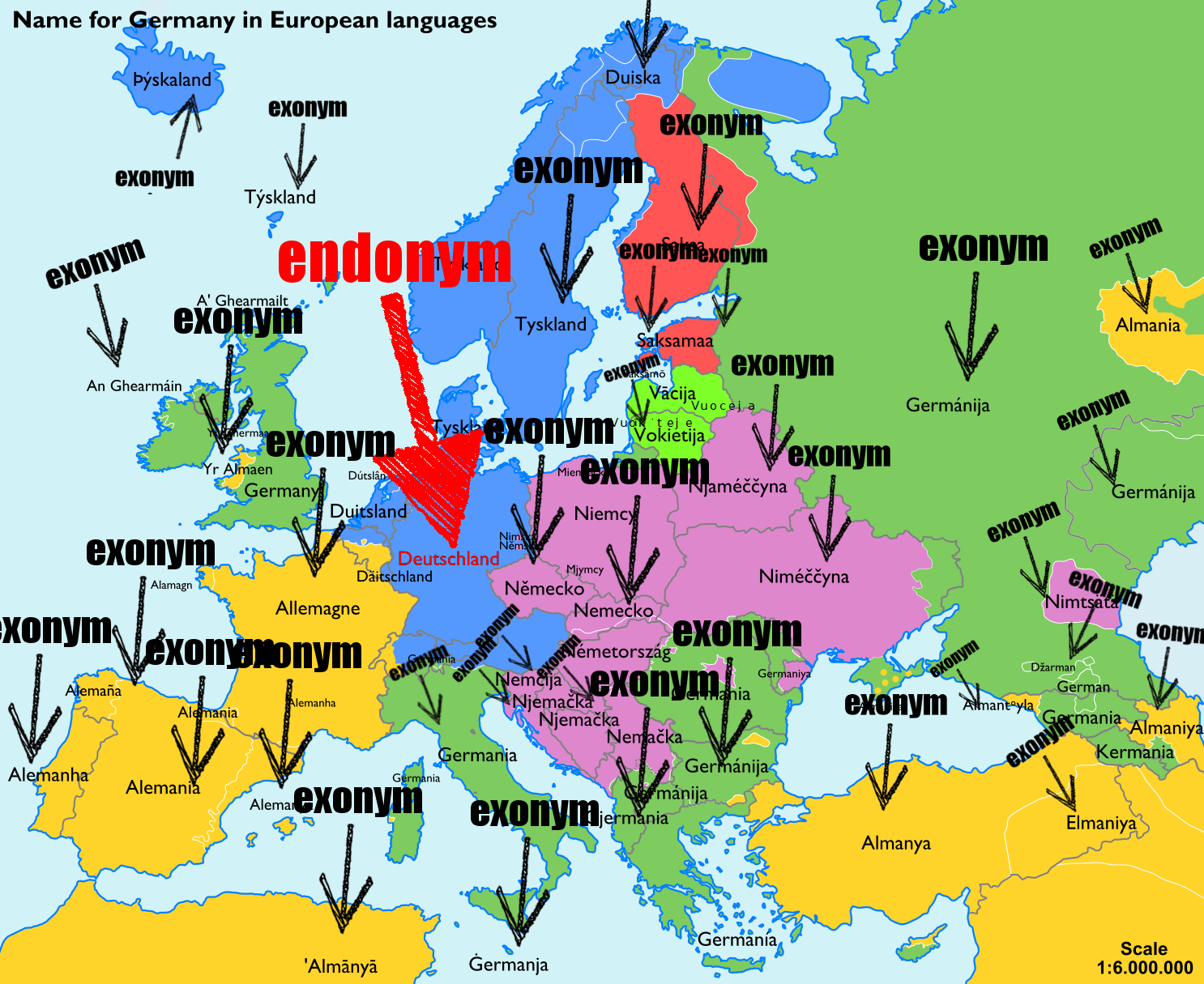

The words “Germany” in English, “Tyskland” in Finnish, “Alman” in Persian, “Nemačka” in Serbian and “Totshi” in Northern Sotho are all exonyms.

Exonyms are words given to countries, cities, populations and regions that are different from the ones used by the people from those countries, cities, populations and regions.

What on earth is an endonym then?

“Germany,” “Tyskland,” “Alman” “Nemačka” and “Totshi” are all exonyms. They’re words that mean “Germany” that weren’t coined by the Germans.

“Deutschland” is an endonym – the word for Germany that the Germans, the people who actually live there, use.

Here’s a map:

Got it?

So now, let’s let the fun begin.

Here are seven facts about exonyms and endonyms.

Fact 1: We tend to see ourselves as normal and everyone else as weird.

Endonyms and exonyms can sometimes reveal a lot about how we think as a country, a tribe or even as a family.

According to Linguistics professor, James A. Matisoff, groups of people tend to equate themselves with being “normal” or even “mankind in general,” while outsiders are “not normal” or “not mankind.”

Sometimes this “us and them” mentality in a community’s use of exonyms and endonyms is expressed through how we perceive language. A lot of exonyms for other nations describe them as being “nonsense-speaking” or even “non speaking.”

Our example with Germany is a case in point. The word for “German” in most Slavic languages is the word “Nemtsi” which is thought to have derived from “Nemy,” which means “mute.” So those from Germany were described as not being able to make a sound.

Meanwhile, the endonym “Slav” is likely to have come from the root word “slovo” meaning “word,” resulting in an endonym gifting Slavs with the power of communication and an exonym denying it to their German neighbours.

Matisoff also observed that some Native American tribes’ endonyms translate into English as “normal people” or “original people,” while outsiders get exonymic terms like “non-speaking” or “nonsense-speaking.”

The Turkish word for “foreigner,” “yabanci,” translates as “from the wild” or “person from the wild,” and although not strictly an exonym, reflects this human tendency to use language to make clear distinctions between “us” and “them.”

Fact 2: Unsurprisingly, colonialism caused many of these.

So how do exonyms and endonyms come about?

Why can’t we all just agree on the name for something and leave it at that?

Well, in some cases, like small towns and cities, we actually do (more on that later).

But in many other cases, we don’t.

Back in the 19th century, Britain had managed to conquer a third of the world with the cunning use of flags (and extreme violence).

All this colonialism was sure to leave a mark on place names. And it did.

Countries like Ivory Coast, Mauritius, the Philippines, Marshall Islands, Jamaica and India are all exonyms (India was originally called Bharat).

Cities, as well as countries, also reveal their colonialist histories; Johannesburg and Lagos (previously known as Eko), for example, still hold onto their colonial names.

Some cities and countries, however, are bucking this trend and have restored their endonyms. Burma is now Myanmar, Bombay is now Mumbai, Ceylon is now Sri Lanka, Swaziland is now Eswatini and the Irish Free State is now, simply, Ireland.

Fact 3: Nations sometimes try to control what outsiders call them.

It isn’t always colonialism that causes changes and creates new exonyms.

Sometimes countries formally request the international community to recognize an old name.

In 1935, for example, Rezah Shah requested that what was known as Persia now be called “Iran” for diplomatic purposes.

The rest of the world took a look at his request and said, “Yeah, why not? Sure!”

More recently, the leader of Turkey has demanded that all Turkish exports bear the sentence “Made in Türkiye” instead of “Made in Turkey.” A lot of commentators have speculated that Turkey wants to banish its exonym (“Turkey”) because of its unflattering association with the bird, turkey.

Thailand also reclaimed its endonym, formally renaming itself from its previous name, “Siam,” which referred to the region more than the country. The term, a Sandskrit exonym, was also potentially derogatory, originally meaning “dark” or “brown,” referring to the skin tone of the people who lived there.

Fact 4: Pronunciation changes and laziness can create exonyms.

Sometimes, instead of reverting to endonyms as a result of political pressure, some countries end up with exonyms simply because of language change and good old fashioned human laziness.

Paris, for example, was originally pronounced with an “s” in French as well as other languages, meaning that everyone was happy with the endonym, “Paris.”

However, as the French language evolved, the “s” was dropped at the ends of a lot of words, words like “Paris,” resulting in millions of frustrated French language learners and, more importantly for this article, in the word for Paris being pronounced without the “s” (but infuriatingly, still spelled with it).

The rest of the world decided not to bother catching up with the French on this one and, in many cases, continue to pronounce the “s.” As the endonym changed, this natural shift in pronunciation created the exonym.

Other examples of exonyms, meanwhile, just evolved out of plain laziness.

When a country or a city has been given a descriptive name (like “the Netherlands,” meaning “flat lands” or “Montenegro,” meaning “black mountain”) instead of adapting the endonym (“Nederland” and “Crna Gora”), countries just prefer to translate it into their own languages.

That’s why “Netherlands” is “Pays-Bas” in French and “Montenegro” is “Karadağ” in Turkish.

Fact 5: Come from a town that doesn’t have an exonym? You’re probably not that important then.

You can sometimes tell how important your hometown is to the outside world based on what they call it.

If you live somewhere that gets to keep its endonym when translated into foreign languages, then … you’re not special!

It feels unintuitive at first, but here’s the logic:

Places like Moscow, Athens or Beijing are of massive geopolitical and historical importance. They have a rich history of diplomatic relationships with various countries and have all come to represent different things to different people around the world.

In a way, the notion of Athens or the notion of Moscow or the notion of Beijing is somewhat subjective.

So those place names tend to take on a local form.

The endonym for Moscow is Moskva, but we call it Moscow, the Germans call it Moskau and the Arabs call it “Msukvu.”

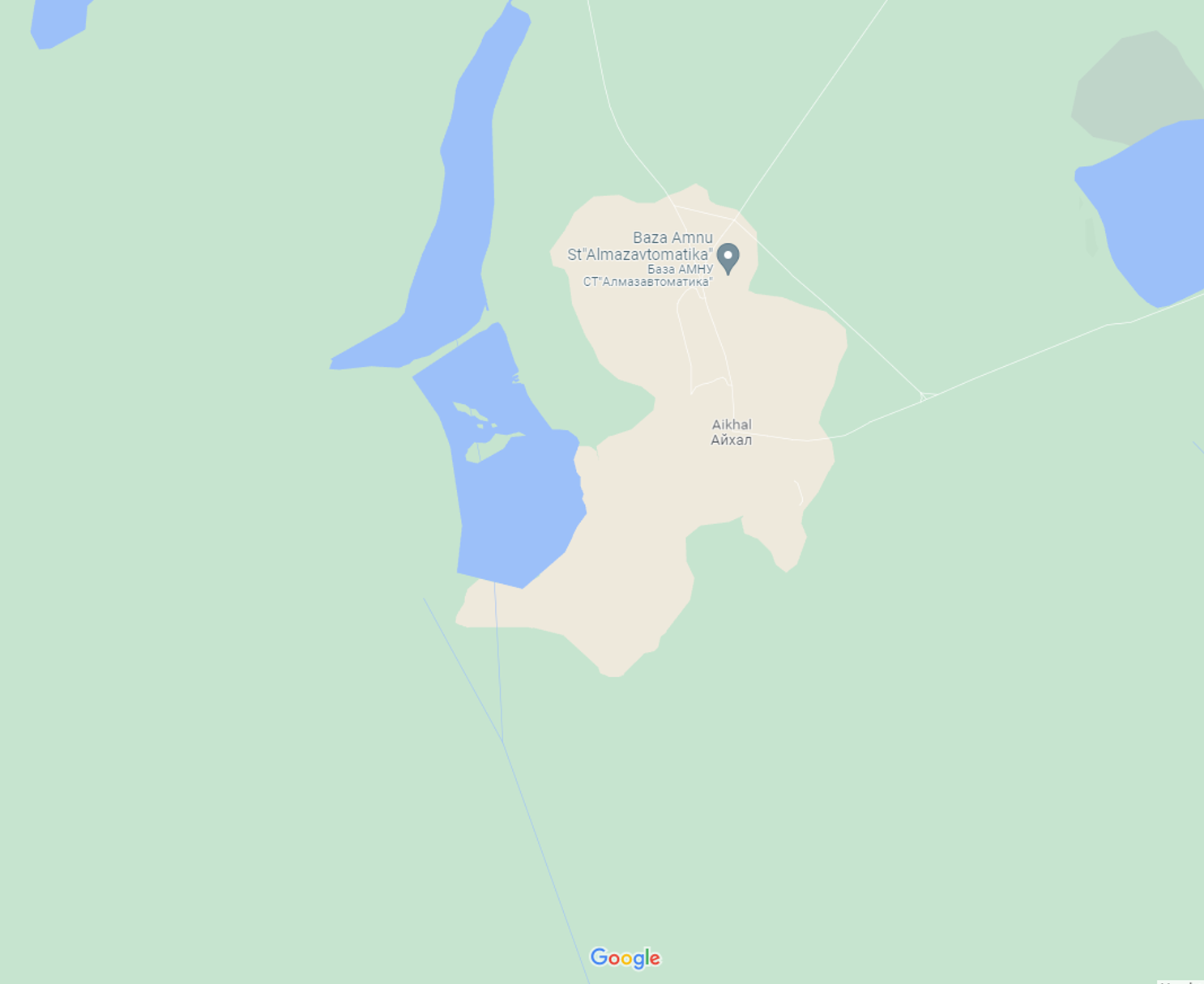

However, if you come from the obscure Siberian town of Aikhal (population: approx 13,000 people), then you’ll find that everyone refers to your home town with its endonym. It’s not special enough to get the exonym treatment.

With this line of thought in mind, it can be quite revealing which capital cities don’t have exonyms. Places like Reykjavik, Ljubljana and Zagreb, perhaps didn’t resonate enough with English speakers to warrant an anglicised version of it.

Clearly, place names in different languages, and whether they take exonyms or endonyms, can reveal a lot about the relationship between the two cultures.

Fact 6: A lot of this can be sensitive and choosing to drop certain exonyms shows positive change.

Let’s listen to James A. Matisoff again:

“Human nature being what it is, exonyms are liable to be pejorative rather than complimentary, especially where there is a real or fancied difference in cultural level between the ingroup and the outgroup.”

Again, we come back to that urge humans have to “other” outsiders. Whether it’s something frivolous like supporting a different football team, listening to the “wrong” kind of music or how you pronounce “gif” (it’s with the soft “g” if you were wondering), or whether it’s something much more weighty like nationality, race, gender, sexual orientation or how able-bodied you are, people have that habit of using language to mark those who are “in” and those who are “out.”

An obvious example is the word “gypsy,” derogatively used to refer to the Roma people.

This exonym, which is related to the word “Egyptian” and comes from the mistaken belief that Roma people all originated from Egypt (their citations included the old testament of the Bible and … no. That’s it), is considered a racial slur by many Roma and is a go-to example of an exonym being offensive to the people it refers to.

We can see the same phenomenon with offensive exonyms like “Lapp” (as in “Lapland”) to refer to the Sami people, “Hottentot” to refer to the Khoekhoe people in South Africa and “Eskimo,” which could refer to either the Inuit people or the Yupik people, who originate from Siberia and Alaska.

And there we have it. Who would’ve thought that the words we use can be so politically charged and can reveal so much about our societies?

I guess, at the end of the day, language matters.

Did you enjoy the article?

If so, you might want to read more from our “Nyms” series.

You might also enjoy my podcast episode titled “The Wizard of Oz, Ingroups and Outgroups, and How Language Reveals What We Really Think”. In this episode I explore the world of exonyms and endonyms.

Gabriel Clark, LOS Consultant & Clark and Miller Co-founder