OK. Let’s start with a little quiz. Which sentences are correct and which ones aren’t?

- I’ve seen so many country.

- She spend all day yesterday talking about giraffes.

- Have you ever seen elephant?

- Your brother is a lawyer, isn’t it?

- I don’t think she know much about that.

- Can you tell me where is the cat?

You might’ve decided that they’re all wrong, right?

Well, you’re right!

But you’re also wrong.

We’ll see why later …

—

Here’s a fun fact I like to cite at dinner parties in order to impress people:

There are now way, way more non-native speakers of English than native speakers.

In fact, some estimates put the proportion of interactions in English

between non-native speakers as high as 80% (Gnutzman, 2000 in Coşkun,

2010, p.1).

But what does that really mean?

Just because they’re using some English, doesn’t mean they’re using it properly, right?

And what do we mean by “proper” English anyway?

Already, with a simple fact, we’ve got all these questions.

The coursebooks all seem to use a certain kind of English – what we

call Standard English (sometimes American, sometimes British, but more

or less all the same). Isn’t that “proper” English?

We should be teaching Standard English … surely!

If we’re not sure about something, we should just ask a native speaker, no? It is their language after all.

Well, “not necessarily” is the answer to that. And here’s why.

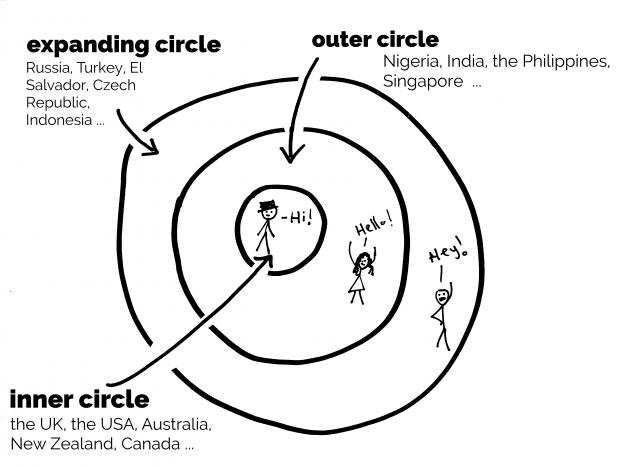

Back in the ‘80s, an Indian academic divided the English-speaking

world into three categories: The inner circle – basically what we call

“native speakers”; the outer circle – people from ex-British colonies

like India and Nigeria, who tend to have a very strong “native-like”

grasp of English; and the expanding circle – everyone else.

Now, remember those sentences at the beginning of this article?

When writing my dissertation, I looked at this “three circles” model

and discovered something quite interesting: not only do people in the

expanding circle make these kinds of “mistakes,” but so do people from

the outer circle AND the inner circle – the so-called native speakers.

You can hear these kinds of “mistakes” all over the English-speaking

world, from Philadelphia to Omsk. From Islamabad to Newcastle.

I kept finding more and more examples of these kinds of mistakes.

Here’s a quick summary:

- I’ve seen so many country.

You can find people using plural modifiers (like “so many”) with

singular nouns (“country”) in parts of the USA, Wales and parts of

England as well as in high-level international communication between non-native speakers.

- She spend all day yesterday talking about giraffes.

Some people don’t always mark the past tense. Some people in the USA, parts of Africa, Singapore and non-native speakers using English in high-level international communication.

- Have you ever seen elephant?

No article? Not a problem for some speakers in the USA, India, parts of Africa, Singapore and non-native speakers using English in high-level international communication.

- Your brother is a lawyer, isn’t it?

“Isn’t it” for any question tag? Yep – you’ll find that in parts of Wales, India, South Africa, parts of Africa and Singapore. Oh yeah, and spoken by non-native speakers using English in high-level international communication.

- I don’t think she know much about that.

You can find the non-use of the third person “-s” in parts of England and in high-level international communication between non-native speakers.

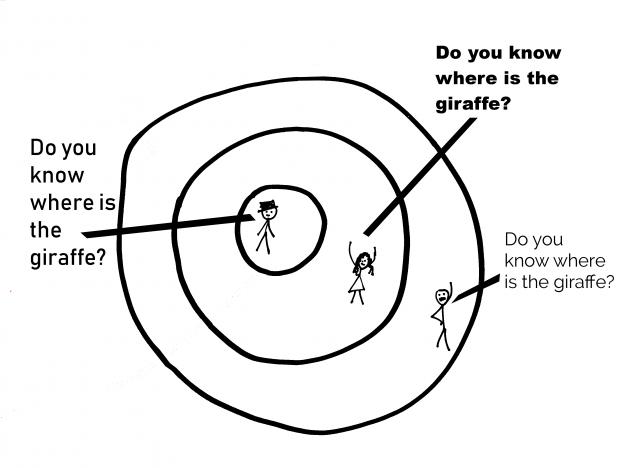

- Can you tell me where is the cat?

No, I can’t. I haven’t seen the cat. I don’t know where is the cat …

or where the cat is. Both these answers seem to be acceptable now.

You get the idea, right?

These “mistakes” don’t matter. We’re all communicating quite fine whether we’ve gone to fairground or gone to the fairground.

There won’t be any problem expressing ourselves whether we don’t know what time it is or whether we don’t know what is the time.

So there appears to be lots of things “wrong” that aren’t. How can

they be wrong if Alistair from Cardiff and Svetlana from Vladivostok are

saying the same thing?

Just because it isn’t Standard English, doesn’t mean it isn’t right. It just means that it isn’t standard.

But none of this is particularly new. English as a Lingua Franca

(ELF) research has been going on for ages (well, since around 2000) and

has uncovered all sorts of features of English that are not standard but

are used successfully by excellent non-native speakers, often in

high-level, high-power corporate jobs.

Things like “the woman which pays me every Tuesday” and “I’m looking

forward to see you later” and “How much time does it take?” (instead of

“how long”) and “Can you borrow me the laptop?”

To put it simply, successful speakers of English are focusing on the

function of the language and less on the grammar – as long as the other

person understands clearly.

Getting the message across. Successful communication.

And that’s fine, right?

But what does that mean for those of us teaching the language and for those of us still learning it?

If you open any coursebook today, you’ll still see that British or

American (or some neutral Standard English) is still being taught. You

won’t see any of these “incorrect” forms that so many people use.

If you ask any school around the world, almost all of them want

“native speakers” as teachers. Sometimes even preferring some random

backpacker from Glasgow to highly trained professionals from Indonesia.

And if you ask the students, many of them will say, “I want to speak like an English person.”

But which English person?

And here’s my question: “Is that what we should be teaching and learning?”

Should English lessons focus on making sure that the students don’t make any more article mistakes?

Should students be corrected every time they get the wrong preposition?

Can’t we focus more on the message than on the grammar?

As teachers, and as students, we really need to be asking ourselves these questions.

And there. I just asked them.

Here is when I play the coward and just leave those questions floating in the air without properly answering them.

I’m going to let Heather Hansen answer them instead!

Gabriel Clark, LOS Consultant & Clark and Miller Co-founder